Articles and News - The Vocal Profiling of Richard III

Yvonne talks at VCN Annual Study Meeting about A Voice For Richard

A review by Susan Page, Voice teacher, Surrey:

‘A Voice for Richard’

Richard III the 3 D King!

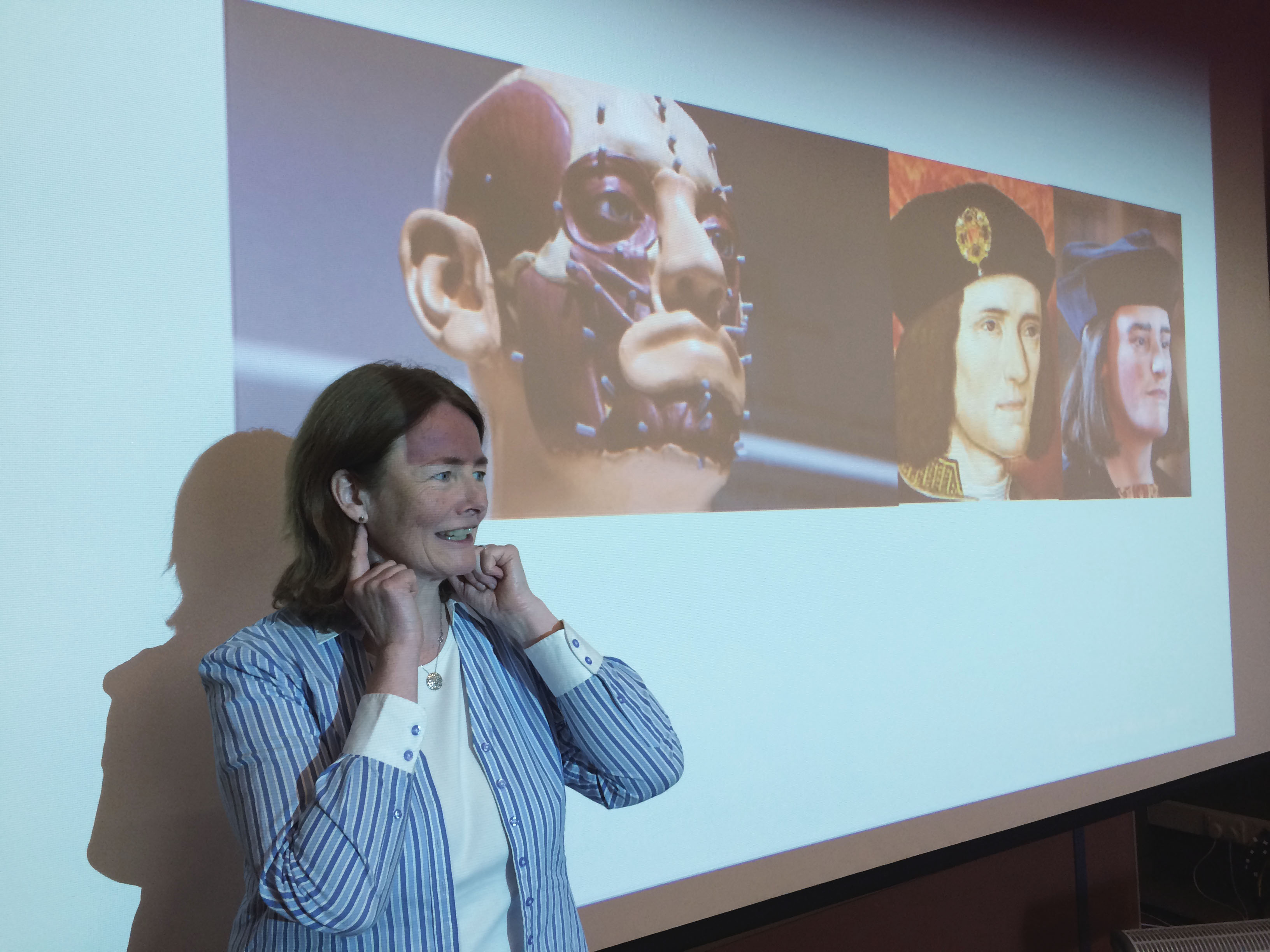

Yvonne Morley enthralled us with the latest updates from her work. Her vibrant presentation detailed the incredible story of how archaeological, scientific and ancestral evidence is being pieced together, jigsaw-like, to give us a vivid picture of Richard III’s appearance and indeed how he might have sounded!…

Read more here

A Voice For Richard – published article

First published in ‘The Ricardian Bulletin – The magazine of the Richard III Society’ March 2015A VOICE for Richard

YVONNE MORLEY

In over 30 years of training voices for actors and public speakers alike, I never cease to marvel at the power of the spoken word. The written word is powerful enough in its own right but how those words sound, when spoken by the one who thought them, can often take things to new levels and even help or hinder relationships with others. For example, we can use a simple greeting like ‘Hello’ to very different effect (perhaps to sound polite, sarcastic, seductive or reprimanding). So the old adage ‘It isn’t what you say, it’s how you say it’ rings as true today as it has ever done.

The spoken word would certainly have had a greater impact in medieval times – an era where it was prioritised over the written word, which was less available to the masses than today. So how might Richard Plantagenet have sounded when he spoke? Are there clues to lead us towards at least part of the answer? Last summer, I was asked to organise the after‐dinner speaker for the Voice Care Network UK’s Annual Study Meeting to be held in September 2014. The event was to be attended by voice coaches, speech and language therapists, singing teachers and others with an interest in voice. With the chosen city being Leicester, I decided that we had to have something on Richard III. We were delighted that Sally Henshaw, Leicestershire branch secretary, was available. The plan was to have her talk to us about the real Richard versus Shakespeare’s brilliant but very inaccurate character, followed by two actors in two different characterisations performing A Voice for Richard.

The Shakespearean Richard would present all the clichés. For example, he would speak in Received Pronunciation (RP, Standard English), which has been the expectation for many an audience in recent history. Yet RP only really came into its own in the 1800s and thereby would be inaccurate both for Shakespeare (1564–1616) as well as for King Richard III (1452–85). Equally in error, I wanted this actor to present a man deformed both in character and physicality with limp, withered arm and ‘nasty’ tone of voice. He would be the ugly and menacing tyrant. Turning to information and inspiration from the incredible discovery of Richard’s remains underneath the car park, I realised that it would take a lot of work and research to even begin to scratch the surface in search of his more authentic voice, let alone offer something in performance befitting the real man.

From left to right actor Paul Lancaster, Sally Henshaw, Yvonne Morley and the actor Tim Charrington. Taken at the Voice Care Network

UK’s Annual Study Meeting, Leicester, September 2014.

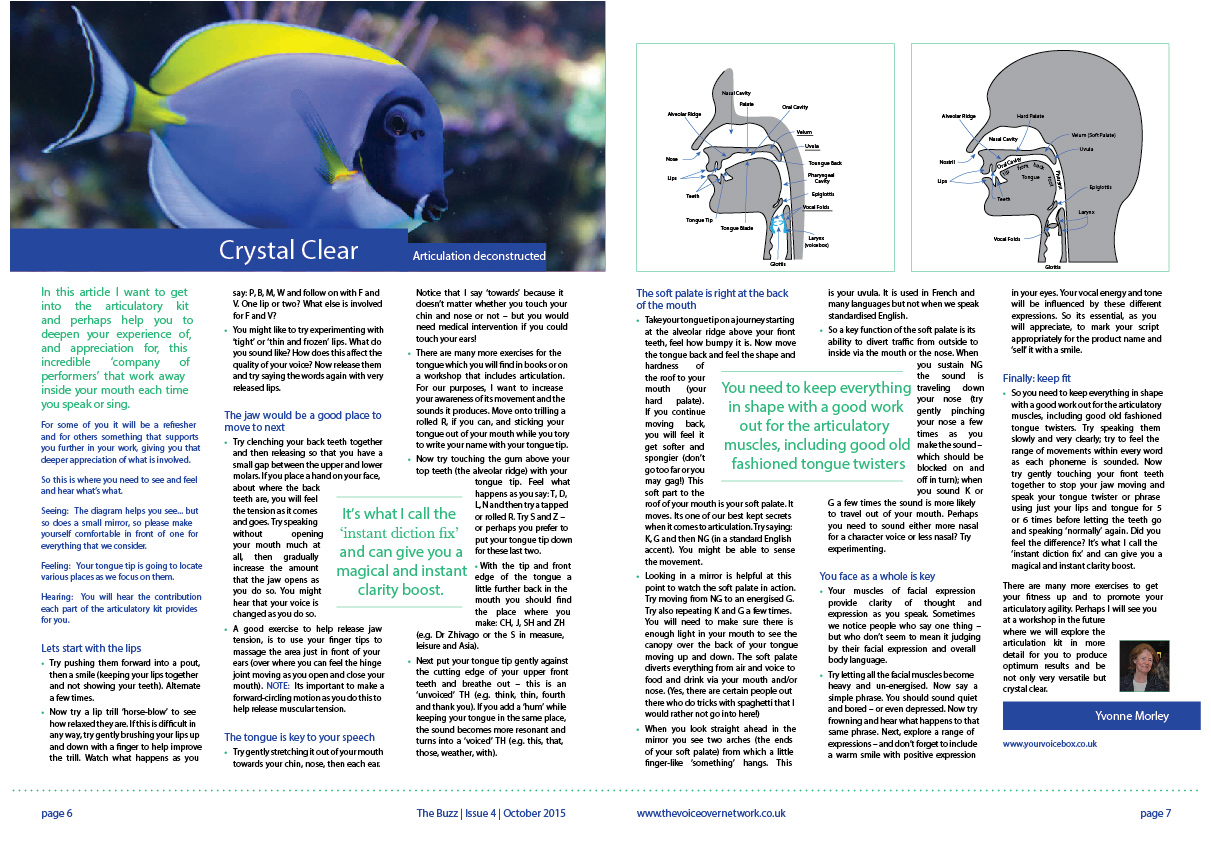

What makes a voice?

At one level it is simply about exhaled breath passing from the lungs up through the airway and meeting resistance from the two vocal folds (cords) inside the voice box (larynx). The ensuing vibrations (many hundreds of times per second, depending on our chosen pitch) are given further amplification and tone as sound moves into resonating cavities within the throat, mouth, nose and sinuses. Turning the vocal sounds into speech requires the addition of jaw, lips, tongue and soft palate to articulate a range of movements that form words. Yet our ‘voice’ is much more than this wind instrument. The spoken word begins with a thought and a need or desire to communicate that thought.

Both actors would need to consider several interlinked elements to create their respective Richards. Each would work with differences in physical size, build, posture, movement, gesture and mannerisms. They would undertake research to include upbringing, social status, health and well‐being. Each would consider an imaginary journey into a typical ‘day in the life of’ their Richard III.

Then the actors would want to understand clues from accent and dialect. Vocal range and resonance would be helped in part by what could be gleaned from accent ‘musicality’ (tune and rhythm) while facial expression and even breathing patterns could help provide further information about character. Facial expression, based on everything from scientific reconstruction to painted portraits, would help to inform ‘voice’, along with knowledge about the broader cultures and worlds in which each, very different, Richard would live.

Then there would be the crucial influence from what I call the ‘inner voice’: each informing two different men’s sets of attitudes, beliefs, values, aspirations and thoughts. We know how much emotional states can create particular facial expression and influence tone of voice in turn. Each Richard’s ‘voice’ – in the broadest sense of that word – would be shaped by these internal influences. Shakespeare, then, was easy. The play, though biased and inaccurate, is well written and helps the actor in search of their character. I was much more interested in getting to know the real man and would need to learn everything I could about him.

Thanks to the work of Professor Caroline Wilkinson, we have a wonderful cranio‐facial reconstruction, showing a kinder face than some might have imagined. Richard’s skull had given a great deal of information about muscle shape and size to enable this reconstruction. It would provide a great resource to understand more about his facial expression and even something about his speech patterns.

‘Richard would get more significantly

out of breath at times

and this would affect his voice

quality in those moments.’

For example, his jaw slightly protrudes forward – not enough to give an underbite – but enough to slightly favour a degree of limitation in how far he opened his mouth while speaking. This is more common in some people than we might imagine and certainly not to be taken as a judgement in any way about their character. Contemporary examples include (to varying degrees) Dr Michael Moseley, Jack Nicholson, Caroline Aherne and Keira Knightly. If Richard’s jaw held tension and wasn’t fully opening as he spoke, vocal resonance would be partially diverted from his mouth and pass down his nose. So he could have had a degree of nasality when he spoke. The accent tuning would probably support this too.

At a physical level then, I was fascinated by the pictures of Richard’s skeleton, especially his spine, jaw and teeth. There was much to learn and not everything could be covered in time for the initial presentation for the VCN but I intended to include what I could.

I was also learning more about his scoliosis. It would not have stopped him riding a horse in a medieval saddle, or being the warrior king, but it meant that he would get more significantly out of breath at times and this would affect his voice quality in those moments, possibly giving him a ‘breathier’ and either a ‘softer’ voice quality or shorter phrasing, with a possible tightness in his sound through increased effort while he was ‘catching’ his breath.

Then there is the issue of his accent. I consulted both an accent coach, Tim Charrington, and Professor David Crystal, who is one of our foremost linguists and a specialist when it comes to recreating Original Pronunciation (OP).

Professor Crystal told me we can say for certain that Richard would have spoken a form of very late Middle English or very Early Modern English. He was living right in the middle of the period known as the Great Vowel Shift, which began around 1400 and continued for a couple of hundred years, with repercussions continuing right down to the present day, in which all the long vowels and diphthongs shifted their qualities. That is why Shakespearean OP sounds reasonably familiar to modern ears, while Chaucerean OP sounds very different. The process would have been well under way by 1452, so Richard would have been growing up in a society where older people were sounding more like Chaucer but younger people were taking the accent in new directions. Which way he would have gone, in the absence of contemporary comment, is unknown. As he moved about the country, his accent would have become mixed, as happens a lot today.

There was certainly a Yorkshire accent at the time, but again, we have no idea what it sounded like. It is important to note that today’s Yorkshire accent would not sound the same. All we have to go on are a few scattered remarks. John of Trevisa comments, at the end of the fifteenth century, on the ‘harsh and unpleasant’ accent of the northerners, especially those in York. (We are still very prejudiced with accent even today and can be seduced or even repulsed by sounds that are not our own.) Chaucer, in his Reeve’s Tale, captures the dialect speech of northerners, showing ‘go’ as ‘ga’, and the like. The word ‘time’ was pronounced ‘teem’ in Middle English and became ‘tame’ in early Modern English. There are detailed examples in Professor Crystal’s Stories of English.1

On Professor Crystal’s advice, I decided to opt for a version of OP that is close to Tyndale – which was a generation later (circa 1525). All the silent consonants, such as the k in ‘know’, for example, would be sounded.2 (Note: at the time of writing this article my research continues to discover how far vowels moved by the late 1400s.)

I am extremely grateful to Sally for putting me in touch with Philippa Langley,3 who generously provided extracts from an early draft of her screenplay to be used for our more authentic Richard to speak.

Stage one

This brought the initial work in progress to that afterdinner event in Leicester last September. Tim Charrington himself gave us a wonderfully menacing Shakespearean Richard (withered arm and limp into the bargain) and then, with a very different physical build – no withered arm, no limp, a scoliosis rather than a curvature of the spine, a very different attitude, accent and voice – Paul Lancaster gave us an initial glimpse of the ‘real’ King.

This more authentic Richard was brought to us in two short scenes from an early draft of the script that Philippa Langley allowed us to use. The first scene showed Richard in prayer, heart‐searching and asking for God’s help before battle.

The second was as he stepped forward to address the army he was about to lead. Here was both a pious, humble man in the sight of God and also someone ready to fight for what he believed in; following the courage of his convictions as an anointed king of England. Here was a man who was inspiring and inspired.

I directed Paul to play the second scene making eye contact with all of us who were his ‘audience’ that evening. Here then was a king who cared for every one of his subjects, regardless of birth or social standing. In clearly audible yet unforced vocal tones was the more authentic accent and voice of a medieval monarch. It was atmospheric and moving to see and hear this ‘glimpse’ of Richard.

Stage two

This is in process and planned for later in 2015. As I write, I am grateful for the ongoing resources and help from many fields of expertise to piece further clues together for Richard’s voice: graphology, forensic sciences, archaeology, history and genetics among them. I am grateful to understand more from the field of dentistry, too. For example, there are particular patterns of teeth grinding that indicate certain levels of anxiety for Richard and even physical discomfort. I am also continuing to investigate further detail for Richard’s accent with help from historical phonologists. I am also searching to find any further clues or accounts from people who either knew him or were at least present to hear Richard speaking in some capacity.

Perhaps you can help? If so I would love to hear from you.

References

- Crystal, D. Stories of English (Overlook Press, 2004)

- Tyndale’s Bible: St. Matthew’s Gospel: read in the Original Pronunciation by David Crystal (Audio CD, British Library, 2013)

- The King’s Grave: The Search for Richard III by Philippa Langley and Michael Jones (John Murray 2013)

Yvonne Morley is a voice teacher and vocal coach. She is an Associate with the National Theatre’s voice department. Freelance work includes training actors and production coaching to include the West End. She also works with lawyers, teachers, politicians and those in the media. She co‐wrote More Care for Your Voice (VCN UK, 1999). For more information visit www.yourvoicebox.co.uk.

A Voice For Richard

A Voice For Richard

Whoever said “History is the version told by the winning side” had a point. It is deeply

hurtful to be misquoted, disbelieved or, worse still, to have reputation put on the line

through unjust accusation and fabrication of the truth.

In the case of the last Plantagenet King: Richard III’s reputation and character were

heavily subjected to the version told by the victor at Bosworth Field: Henry Tudor. With

Richard’s brutal death on that day in 1485, the portrait of a monster was created. It was

initially sketched by the next monarch, Henry VII and later given rich colours and bold

textures by that brilliant dramatist and poet: William Shakespeare. From the play bearing

Richard’s name crawled a malicious, crook-backed, evil creature … murderous and cruel.

Our view of him has subsequently been prejudiced by this excellent but fictional story and

believed by the masses for over 500 years.

Thanks to the dedicated work of some, not least The Richard the Third Society, evidence

shows a very different person. Richard was a loving husband and father, a man of prayer,

and an honourable nobleman who desired justice for rich and poor alike. Richard III gave

us our jury system, bail and the beginning of what we now call Legal Aid. He was

chivalrous. He was the last warrior King. Notably, he inspired the loyalty of many.

The dedication and conviction of Philippa Langley, screenwriter, who spent years on a

quest for the truth, resulted in the most amazing discovery of all on 25th August 2012.

Beneath a car park in Leicester within the remains of the Grey Friars church, and on the

very first morning of the excavations, the mortal remains of King Richard III were found. *

Later, with an exact DNA match and a range of scientific tests to erase any lingering

doubt, the verdict was conclusive. Here indeed lay Richard Plantagenet, hurriedly placed

in an insufficient grave.

Many months have passed since that extraordinary discovery. In the interim, preparations

have been underway to give Richard III the honourable burial, long overdue, that befits an

English King. He will be interred within Leicester Cathedral in spring 2015.

“Words, words, words” (Hamlet)

Words are powerful. The writer, director and actor know this. They create for better or

worse and often resonate for a long time to come. They both made and later marred King

Richard.

In over thirty years of teaching voice, it never ceases to be anything but a privilege to step

into the rehearsal room and explore the written text with a company of actors as they work

to create the world of the story given to them by the writer.

To authentically create a role, an actor often works towards degrees of transformation in

their physicality, personality and vocality. Each actor is unique; each director has a

different approach. To that end, as the voice coach on hand, I need to use a range of skills

and techniques to support the rehearsal process. There can’t be a “one size fits all”

approach.

One of my coaching resources is “Character Voice”. This approach has evolved over 15

years and is inspired by the work of phoneticians, dialect coaches, linguists, singers,

actors and movement specialists – to name but a few. It serves the performer in a range of

ways including how to build a vocal creation from scratch. It is especially reliable for the

actor who is called upon to replicate another’s voice. It relies upon the clues found in an

individual’s physicality and personality, it is informed by research into accent, dialect, pitch

range, resonance and tonal qualities, articulation patterns, physical posture, breathing and

many other “ingredients” which are placed into the creative melting pot.

So when it fell to me to provide the after dinner entertainment for the Voice Care Network

UK’s Annual Study Meeting in Leicester this year, Richard III was foremost in my mind.

Sally Henshaw, Leicester Branch Secretary of the Richard the Third Society, initially spoke

to us about the authentic King. We were very fortunate to have her. Following her detailed

talk about him, two actors presented work that I had undertaken with them to find “A Voice

For Richard”.

I had thought that an audience of voice teachers and Speech and Language therapists

would find this interesting. Weeks ahead of that weekend, Sally had been generously on

hand to answer my many questions about the “real” man. I was also working through a

number of auditions to find suitable actors able to portray two versions of Richard:

Shakespeare’s “bunch-backed toad” and the “authentic” King. I was fascinated by the

pictures of Richard’s skeleton, especially his jaw and teeth. The reconstruction of his face

by Professor Caroline Wilkinson had inspired the beginnings of my own quest to search for

clues into his articulation patterns, accent options and the strength and size of his facial

muscles. I am very grateful to Philippa Langley for generously allowing extracts from an

early draft of her screenplay about Richard to serve as a refreshingly different script to the

much quoted and brilliant text that Shakespeare gives his own fictional creation.

A good actor changes both on the inside and the outside. They transform the atmosphere,

moment by moment, either within that space we call a “theatre”, in front of the moving

camera or behind the microphone in the recording studio. Stanislavski gave the actor a

mantra: “I am”. Not just doing or demonstrating but “becoming”. So, for example, the

physicality of the original and the range of notes on the vocal keyboard may be marginally

or more significantly different from their own. The personality will always need a journey for

soul and even spirit to embrace and to “become”. This then was a fascinating process to

apply initial clues and begin to work out the first stages of “vocality”, physicality, personality

and – to use actor’s jargon – “the back story” for this much maligned king.

There is much more that I intend to write as the work progresses with plans to present a

short talk alongside actors performing “A Voice for Richard” (stage two) early in 2015. I am

grateful for the resources from many of the experts who have been working on the

evidence produced from archaeology, graphology, genetics and forensics. Thanks to the

work of Professor Caroline Wilkinson, we can even have a reconstructed model of his

face. Other information comes from clues within Richard’s skeleton, letters he wrote and

his own precious prayer journal: Richard’s “Book of Hours”.

“Stage one”, as I like to call it, brought the initial work in progress to that after-dinner event

in Leicester for members of the Voice Care Network UK. Tim Charrington gave us a

wonderfully menacing “Shakespearean” Richard and then, with a very different physical

build: no withered arm, no limp, a scoliosis rather than a curvature of the spine and a very

different attitude, accent and voice – Paul Lancaster gave us an initial glimpse of the real

King. It was moving to see and hear him.

My journey has barely begun to find a Voice for Richard.

* The King’s Grave: The Search for Richard III by Philippa Langley and Michael Jones (John Murray 2013)